Cambridge Seniors: Shiao Shen Yu

Hear Shiao Shen Yu’s voice here.

Shiao is a force.

There’s no two ways about it. You’d have to be, to survive being one of the last of eight children born in the middle of Japan’s occupation of China. You’d have to be, to survive both that war and the ensuing Maoist Revolution in China. To escape to Taiwan. To earn a place in one of the nation’s most competitive schools, despite having mostly missed school yourself as a child of war; and to become peerlessly fluent in your second language.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Shiao reached out for an interview after seeing my poster in Youville House. When she greeted me at the entrance a few days later for our first interview, she giggled and offered me a tiny paper origami crane that she’d folded for me that morning. She’s an origami enthusiast, which, given her father’s history, makes sense.

Shiao was born in either 1939 or 1940, depending on who you ask. She was born at her father’s ancestral home. Her father was a brilliant architect, who was born Chinese and then educated from his early teen years onward in Japan, tagging along when his brother had gotten a scholarship from China to study abroad. Shiao’s father ended up being so talented that he matriculated into Japan’s most famous university, Tokyo University.

Shiao’s mother was the only girl she knew of her own class who did not have her feet bound. (For centuries, upper-class girls would undergo painful torture, having their feet broken and bound to achieve what was called “lily feet,” which was a mark of femininity). When a servant had begun to bind her feet, her father threw the servant off and declared that he’d never let her feet be bound. Shiao’s mother was made fun of for her big feet, which were about a size 5 ½.

Because of Shiao’s father’s fluency in Japanese, the Japanese National Army tried to recruit him to serve them in the Second World War. He refused. A Japanese doctor took over the family home that Shiao’s father had had built.

Shiao drawing out a map of her and her parents’ birthplaces. “Pretty good, right? That’s because I’m a professional [teacher].”

When Shiao was about five years old, a new nanny named Wang Ma came into her life. (To this day, it makes Shiao tear up, speaking of Wang Ma). Shiao didn’t feel particularly wanted by her mother, who had to rear nine children. Wang Ma, having lost her husband, son, and daughter, in the Nanking (or Nanjing) Massacre, immediately swept Shiao up into care as a kind of surrogate daughter. Wang Ma had escaped rape by Japanese soldiers by pressing her face against a soldier’s sword and mutilating herself. Her late daughter was Shiao’s age, which doubtless helped determine their bond.

Shiao remembers hiding on the family property in the evenings sometimes, when Japanese soldiers would roam around looking for women to rape. Her maids and nannies were young, targets for sexual violence. One time a soldier, bayoneting a pile of hay where some members of the family were hiding, came so close to getting one of Shiao’s maids that the young woman felt it graze her ear. Miraculously, they all survived.

After the war, the strife didn’t end. Maoists were taking power in China, and Shiao’s family, owning land as they did, were targets.

Shiao demonstrates a Maoist dance she learned during her brief time in school in mainland China.

Shiao’s paternal grandfather was hanged. The family resolved to go to Taiwan at Shiao’s mother’s insistence. The family split up, each parent taking a few children. At first, Shiao’s father wasn’t able to secure passage on a ship leaving from Tsingtao. He “was a gentleman,” and didn’t shove other people hard enough to make it on the boat. The second time around, he managed to through. He advised his wife not to book first class tickets, but instead to book third class ones and to use the extra cash to hire strongmen who could insure that she and her children would be able to board.

During the voyage, Shiao’s mother never left her bed nor took off her heavy padded outfit, to Shiao’s confusion. But when they disembarked in Taiwan, her mother undressed out of her “long pants” in public. Shiao was mortified that her mother was underdressing, until she looked around and saw other women doing the same. They had all sewn precious metals and jewelry into the lining of their outfits – enough to start a new life.

Shiao’s mother claimed that she was born in 1939. Since rice portions were allocated by age, having a ten-year-old meant more rice. The family lived in poverty, many days not being able to afford meat or any side dishes.

Shiao had hardly attended school, but her older siblings saw that she was highly intelligent. They decided to have her take the entrance exams for a coveted spot at one of the high-ranking public schools. Her older siblings tutored her and she made it into the second-best school in Taiwan. She regularly placed in the top ranks of her class, but didn’t have a perfect score because she couldn’t participate in gym. She couldn’t run due to an illness earlier in childhood.

She made it into a top university, but her family couldn’t afford the fees. She underwent training to be a teacher, and completed her student teacher training, before re-attending the university as a regular student a few years later. Being three years older than her classmates, she found it awkward to socialize. When she was about twenty-four, she met a man who was about to leave for Libya to work as a doctor. She was eager to get out of her parents’ home, so she married him and took off for Libya.

His work took them to Canada next, where Shiao gave birth to two daughters. Her husband, who’d been born in mainland China and worshipped Mao Zedong, put up Mao’s portrait in their home and demanded the little girls bow to him. He wanted to return to mainland China. Shiao adamantly refused. That’s what he began to hit her. As she recounts: “I wouldn’t stand for it. I’m a strong woman.” So she filed for divorce, and he abandoned the family for China. He never communicated with them again.

At a dance one evening in Canada, she met a Swiss-German man. He became her second husband. He missed the mountains, so they decided to move down to Colorado. She started work as a bookkeeper, and was prized at work, saving her company tons of money in taxes. She also received her certification and began working as a teacher.

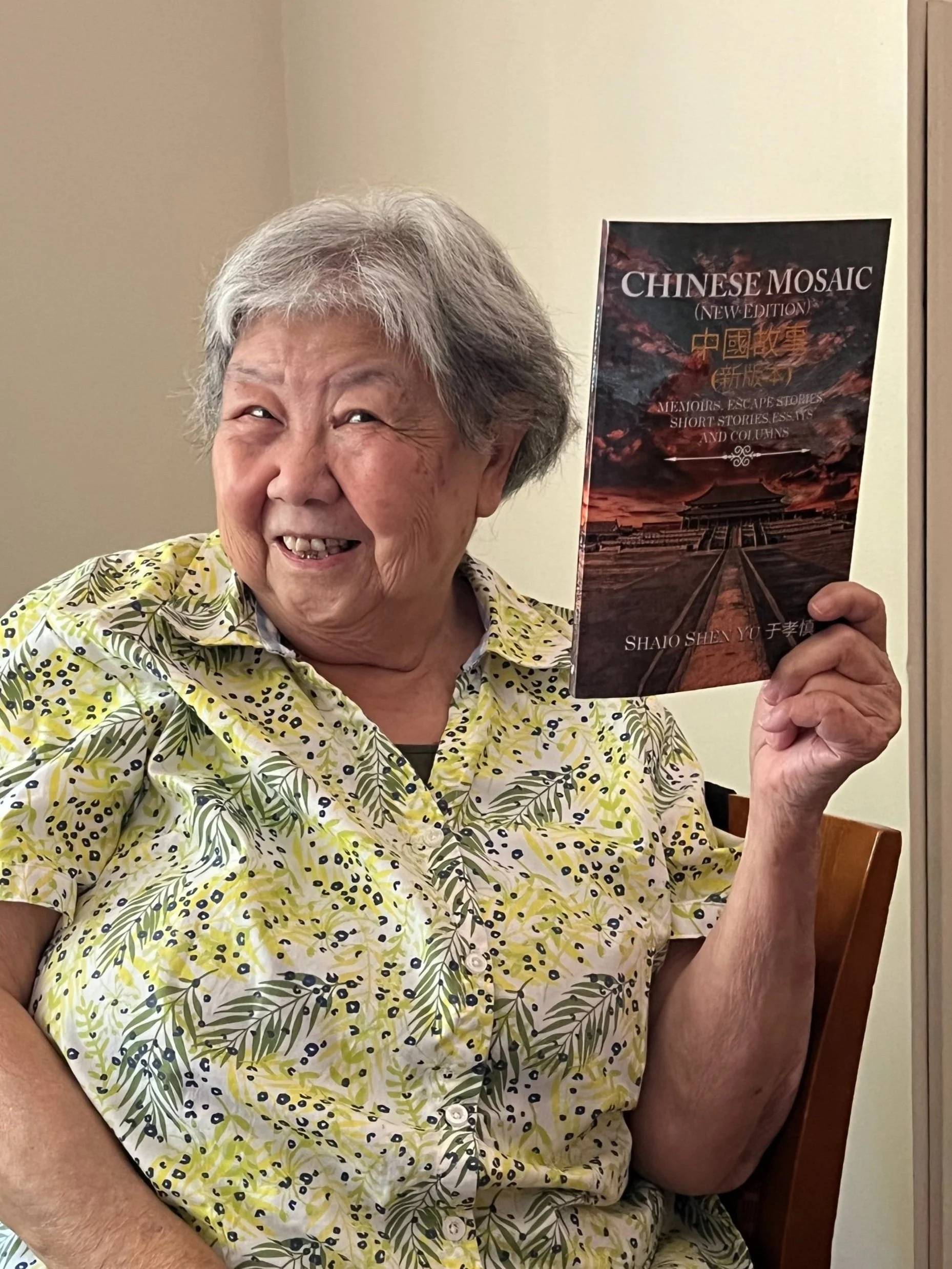

Despite being fluent in English – anyone who reads a page of her memoir or other writings can attest– she was often underestimated for her language abilities because of her accent. But she began taking writing classes. Her mother had wanted to be a writer, and had written some over the years. Shiao took up the mantle with enviable dedication. She achieved success as a contributor to local newspapers, writing on Chinese culture and history. She told me that her second husband couldn’t much take her notoreity, so they divorced. She has since published two books: Chinese Mosaic: Memoirs, Short Stories, Essays, and Columns, which is available for purchase online; and The Two Swordmasters and Two Women.

Shiao took care of her own mother for about seven years at the end of her mother’s life. She was a dutiful daughter but keenly felt the strain of having to translate for her mother, who could not navigate life in English. Having tutored her two daughters from a young age, especially in Mathematics, Shiao sent both of them off to top universities. One daughter became a lawyer; the other, an academic.

Family photos: Shiao’s mother at left, and also in center photo surrounded by her laughing daughters. A young picture of Shiao (right).

Shiao went back to visit China a couple of times. In 2011, the Chinese government helped offer discount fares in honor of the centennial of the Xinhai Revolution ending the last imperial dynasty. Shiao and her sisters traveled together on a whirlwind tour.

These days she’s seizing life by the reins. In spring, 2022, she purchased an MBTA pass so she could cover as much of Boston as possible. She continues to write. She is also learning the piano, continuing with her origami, and loves to watch Chinese historical dramas she can find on YouTube. Much more of her story can be found in her book, Chinese Mosaic, copies of which are available to purchase at the exhibition at 34 JFK St..